Allulose: The “New Sweetener” on the Block—Should You Use It?

Heard about Allulose but not sure if it's good for you? Discover how this sweetener can satisfy your holiday cravings without the sugar crash!

The holidays bring a gentle blend of joy and nostalgia—a time to cozy up with warm drinks, indulge in sweet treats, and enjoy the comforting routines that make this season special. As our kitchens fill with the scent of baking, it’s nice to find ways to enjoy these treats in ways that nourish our bodies, so January doesn’t have to mean extreme dieting or ‘detoxing’ 🤣.

I’ve covered the usual suspects—erythritol, monk fruit, and maple syrup—in a previous post, so feel free to check that out if you’re interested in those sweeteners. Today, though, I wanted to shine a spotlight on the new kid on the block everyone’s asking me about—Allulose.

What is Allulose?

Think of allulose as sugar’s hip cousin. It has about 70% of sugar’s sweetness, so you’d want to replace sugar in any recipe with 1.4 times the amount of allulose. For example, if your recipe calls for 1 cup of sugar, you’d use 1.4 cups of allulose. Allulose occurs naturally in tiny amounts in foods like figs, wheat, and molasses, but most of what you’ll find in stores in bags is derived from corn - more on what that means later.

Pros:

Won’t Spike Blood Sugar or Insulin: Structurally similar to fructose, allulose lets you enjoy sweetness without the blood sugar or insulin spikes.

Low-Calorie Sweetness: Allulose has only 10% of the calories of regular sugar

No Weird Aftertaste: Allulose tastes very similar to sugar 😋

Ok, but isn’t fructose bad for you? Isn’t that why we avoid high fructose corn syrup?

Great question! There’s a lot of confusion around fructose, so let’s unpack this.

Fructose in whole fruits is combined with fiber, water, antioxidants, and minerals, which makes it a thumbs up in my book. Don’t fear whole fruits - believe it or not, the evidence overwhelmingly suggests that people who eat whole fruits tend to have better blood sugar control, even those with diabetes.1 It’s hard to overdo it with whole fruits because the fiber and water content help us feel full and provide ‘natural’ portion control.

The issue arises when we start altering whole fruits, such as juicing, drying, or—worst of all—concentrating glucose and fructose into syrups like agave or high fructose corn syrup. In these highly processed forms, fructose is easy to overconsume, and excess fructose in these processed forms has been linked to fatty liver, which is essentially fat accumulation in the liver.

So what if I have fat in my liver, you ask?

Fat accumulation in the liver can contribute to insulin resistance, prediabetes, and type 2 diabetes. It’s one of the primary reasons for the epidemic of poor blood sugar control we’re seeing today. Left untreated, fatty liver can progress to cirrhosis, which causes irreversible damage and can ultimately lead to liver failure requiring a transplant.

Serious stuff.

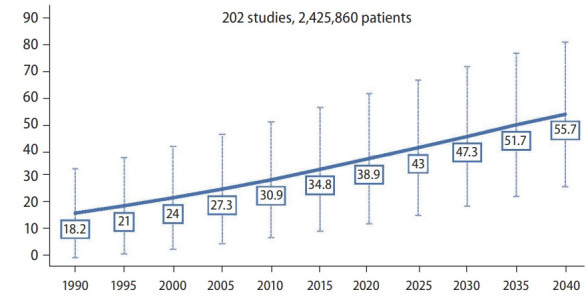

When I was a medical student, most cases of fatty liver disease I saw were due to excess alcohol. But as I moved into my practice as a family physician, I began to see more and more cases unrelated to alcohol—an alarming shift mirrored in national health data 📈.

According to NHANES, the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in U.S. adults jumped from 20% (1988–1994) to 33.2% (2009–2012).2 In other words, 1 in 3 American adults now has fatty liver disease 🚨.

This increase is largely due to the standard American diet, coupled with lifestyle factors and environmental exposures that burden the liver. And even more concerning? About 18% of teens now have fatty liver, which sets the stage for chronic diseases in the future. Reversing this trend is essential.

P.S. Speaking of fructose, if there’s one takeaway here, it’s this: Agave is NOT a healthy sweetener. Agave nectar can contain 70–90% fructose, depending on the brand and processing, while high fructose corn syrup—already flagged as harmful—contains only 55% fructose 🤯. If you’re avoiding high fructose corn syrup, it’s wise to steer clear of agave too. Small amounts are fine, but excess fructose is tough on the liver and should be limited.

Back to Allulose

Unlike fructose, which is metabolized in the liver, allulose passes through our bodies largely unaltered and is mainly excreted through our urine.